Who is God?

Who is God?

When the great prophet Moses asked this question, God replied to him: ‘I AM THAT I AM’ or ‘I am the existing one’ (אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה / ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν).

God, then, is the one infinite and eternal source of all that is, the source of existence itself. God is not a being, but is being itself. God is not a part of the universe, nor is he the universe itself, nor does he exist alongside the universe, but all things continuously receive their being from God who is the source of all existence. There can only be one such source, which is why belief in only one God is the bedrock of the Christian faith.

In the Liturgy, we confess God to be ‘ineffable, incomprehensible, invisible, inconceivable, ever existing, eternally the same’. Yet, despite being absolutely transcendent, he is also ‘everywhere present and filling all things’; although he is beyond human comprehension, he reveals himself to his creation. The Bible says he desires that all people ‘should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him. He is actually not far from each one of us, for “In him we live and move and have our being”’ (Acts 17:27).

God is love

(The Holy Trinity)

The Bible tells us that ‘God is love’ (1 John 4:8), not only that he has love for his creation, but that he is love; love defines his eternal being. God created us in love, and it is through love that we come to know him.

True love, of course, is something you give and have for another. Self-love is no love at all, and if God is love only in relation to his creation, this makes him dependent on something external to himself — he is no longer perfect, no longer absolute, no longer…God. So how can we then say that ‘God is love’?

The Bible, and the lived experience of the Church throughout the ages, reveals to us one God who exists eternally as a communion of three hypostases (subjects of existence): Father, Son (Logos), and Holy Spirit. This is what we mean when we refer to the Holy Trinity.

Sincere there is nothing in creation that is similar or analogous to God, every analogy will fail and lead us astray if taken too far. Indeed, anything we say about God using human language and concepts are at best symbols and approximations. However, certain analogies can nonetheless be helpful in understanding aspects of our idea of God. One image used frequently in the liturgical texts of the Church is that of the nous (mind), from which is born the logos (word, or rational principle) and action. There is only one mind and one operation, and yet we can distinguish three different principles, although these cannot be separated or exist independently of one another. Another image is that of a flame emitting heat and light. Again, we can distinguish three different principles here, but there is only one flame. Emitting heat and light is what makes the flame a flame — it is natural to it — and you wouldn’t have heat or light without the flame.

In the same way, the Logos and the Spirit proceed naturally from God the Father from all eternity. There was never a point in time when the Logos or Spirit did not exist. God was always a Trinity.

God is thus both one and three. Not in a contradictory way — he is not one in the same way that he is three — he is one in one respect (essence) and three in another (hypostasis). There is one living God (the Father) with his one divine Life (the Son) and his one Spirit of Life. There is one True God (the Father) with his one divine Truth (the Son) and his one Spirit of Truth, and so on. The three divine Persons are equal and alike in every way, having their being in one another, and sharing one divine nature which is not made up of parts, one divine will, one divine activity, one divine life in an eternal communion of love for one another.

‘In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son’ (1 John 4:10), Jesus Christ.

Who am I and why am I here?

‘Partakers of the Divine Nature’

God the Holy Trinity exists eternally as a communion of love, and it is out of this love that he created the world and, above all, humankind. God did not create us to be disposable pawns on a cosmic chessboard, nor does he have any need for servants, helpers, or worshipers. God created us in order to share his love with us, and to make us “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4).

In the Book of Genesis, we learn that humankind is unique among all creatures in that God has made us in his own image, with the potential to attain his likeness. Attaining this likeness, becoming like God, is the goal and purpose of every human being. In the Orthodox tradition, we refer to this process as theosis; we become by grace what God is by nature.

Humankind and creation

Humankind is also unique in another sense; namely, in that we belong to both the visible and invisible realms of creation — we have both a physical body and a spirit.

The human being, then, stands at the centre of the created world, uniting the physical and spiritual parts of creation, and acting as the link between God and the world.

In the eyes of God, each human person has infinite value and a lofty calling.

The Fall

As we said, we were created out of love, to love, and be loved. But love is only love when it is freely chosen. In order for true love to exist, then, there also has to be the possibility of rejection — in order for union with God to be possible, separation from God also has to be possible.

The story of Adam and Eve, their disobedience and eviction from Paradise, is an expression of this reality. Instead of reciprocating God’s love and finding their fulfilment in him, humankind chose self-worship and self-deification (the eating from the Tree of Knowledge of God and Evil symbolises, among other things, man usurping the place of God as the ultimate criterion and reference point for what is right and wrong, true and false) and turned away from God.

Since God is the source of life, cutting ourselves off from that source naturally led to death: first spiritual, then physical. Moreover, since mankind is the link between God and creation, the fall of man did not just affect him, but the entire world.

This state of separation from God — into which we are all born, and which accounts for all the brokenness and injustice in our world — is what we call ‘sin’. The Greek word for sin is hamartía, is an archery term that literally means ‘missing the mark’ (the Hebrew word חָטָא has the same meaning). Union with God is our target, any act or disposition that leads us away from that goal of union is hamartía, sin.

Salvation

God’s love, however, is unconditional. Mankind rejected him, but he did not reject mankind. Quite the contrary, the Bible tells us that ‘For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life’ (John 3:16). As we pray at almost every Divine Liturgy,

You brought us out of non-existence into being, and when we had fallen you raised us up again, and left nothing undone until you had brought us up to heaven and had granted us your Kingdom that is to come.

In order to bridge the gap separating God and man, God himself — in the person of the eternal Word — became man, uniting himself with our human nature, and conquered our enemy — sin and death — by dying on the Cross and rising from the dead on the third day.

Who is Jesus Christ?

What is the Bible?

What is the Bible?

The Bible is not one book, but a collection of many different books written by many different authors over a period of many centuries under the divine inspiration of the Holy Spirit. In the Bible we find books of history, law, prophecy, poetry, song, prayer, instruction, and symbolic imagery, among other things.

Despite the varied content of the books, they all have one unified message: the love of God for mankind. Specifically, they deal with mankind’s falling away from God and their restoration back to him through the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.

We typically divide the Bible into two sections:

- The Old Testament, which contains all the books written before the coming of Christ.

- The New Testament, which contains all the books written after the coming of Christ.

Most of the books of the Old Testament are written in Hebrew, while the books of the New Testament were written in Greek, which was the common language in the eastern Mediterranean at the time of Jesus.

The books of the Bible

The Old Testament

The books of the Old Testament are traditionally divided into three groups — the Torah (Law), the Prophets, and the Writings (see Luke 24:44). Today, however, it is more common to divide them into four groups — the Torah, the Historical Books, the Writings (or Wisdom Books), and the Prophets.

Torah

1. Genesis, 2. Exodus, 3. Leviticus, 4. Numbers, 5. Deuteronomy

Genesis begins with the story of creation and the fall of mankind. It then continues with the stories of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Israel) with his twelve sons, and how God promises to make them a nation through which the entire world shall be restored by bringing forth the Woman who would give birth to the Saviour.

Exodus tells the story of the Passover — Moses delivering his people from slavery in Egypt, and their wandering through the desert in preparation to enter the Promised Land. This story of freedom from slavery points to the true Passover: Jesus Christ saving us from slavery to death and sin by his death and resurrection.

While wandering in the desert, the Israelites were given the 10 Commandments and the rest of the Law of Moses. This Law contained not only moral guidance, but also ritual prescriptions about things such as how to worship, how to dress, what to eat, etc. The purpose of these laws, which is a primary focus of the remaining books, was to give every aspect of life a prophetic meaning.

The Historical Books

6. Joshua (Jesus), 7. Judges, 8. Ruth, 9. I Kingdoms (1 Samuel), 10. II Kingdoms (2 Samuel), 11. III Kingdoms (1 Kings), 12. IV Kingdoms (2 Kings), 13. I Chronicles, 14. II Chronicles, 15. I Esdras, 16. II Esdras (Ezra), 17. Nehemiah, 18. Tobit, 19. Judith, 20. Esther, 21. I Maccabees, 22. II Maccabees, 23. III Maccabees

The historical books describe the entry of God’s people into the Promised Land, and the establishment of Jerusalem as the holy city and home to the Temple. They also describe later exiles and returns, detructions and restorations.

The Writings

24. Psalms, 25. Job, 26. Proverbs, 27. Ecclesiastes, 28. Song of Songs, 29. Wisdom of Solomon, 30. Wisdom of Sirach

The Book of Psalms is the main prayer book of the Church, and forms the bedrock of all our services; Proverbs, Wisdom of Solomon, and Sirach are books of moral instructions; Job and Ecclesiastes are meditations on the human condition, vanity and suffering; while the Song of Songs is a symbolic expression of God’s love for the Church, told through the voice of two lovers.

The Prophets

31. Hosea, 32. Amos, 33. Micah, 34. Joel, 35. Obadiah, 36. Jonah, 37. Nahum, 38. Habakkuk, 39. Zephaniah, 40. Haggai, 41. Zechariah, 42. Malachi, 43. Isaiah, 44. Jeremiah, 45. Baruch, 46. Lamentations, 47. Epistle of Jeremiah, 48. Ezekiel, 49. Daniel

The word ‘prophet’ means someone who speaks on God’s behalf. The primary task of the prophet is to be the conscience of the Church, of God’s People, calling them back to the straight path whenever they have strayed. In so doing, they issue warnings and also offer hope (in this context revealing future events).

The books of the prophets speak both to their immediate context, with words of warning and comfort, but also point to the future, particularly to the coming of Christ.

(Appendix)

50. IV Maccabees

The eleven books listed in italics are known as the deuterocanonical books (‘books of the secondary canon’). The Orthodox Church considers these books sacred Scripture, which may be read liturgically in church, but affords them a lesser status than the other 39 books. In many modern English editions of the Bible, most of which are Protestant publications, these books are either omitted or placed in an appendix titled Apocrypha.

The New Testament

The New Testament contains 27 books (most of which are actually letters), also typically divided into four sections:

The Gospel

1. According to Matthew, 2. According to Mark, 3. According to Luke, 4. According to John.

Gospel (Evangélion) means ‘Good news’. Strictly speaking, these four books are not ‘four Gospels’, but four different records of the one Gospel, the one message, of salvation in Jesus Christ. They describe the earthly life and teachings of our Lord..

History of the early Church

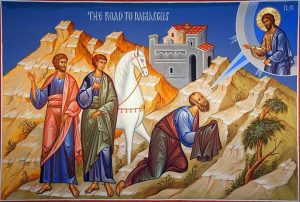

5. The Acts of the Apostles

Also a book of St Luke, Acts continues the story told in Luke’s Gospel. It begins with the Lord’s Ascension into heaven and his sending down the Holy Spirit on the Apostles. It then follows them on their missionary journeys, recording the first three decades of Church history.

The Pauline Epistles

6. Romans, 7. I Corinthians, 8. II Corinthians, 9. Galatians, 10. Ephesians, 11. Philippians, 12. Colossians, 13. I Thessalonians, 14. II Thessalonians, 15. I Timothy, 16. II Timothy, 17. Titus, 18. Philemon, 19. Hebrews

These are a number of letters written by the Apostle Paul to the various church communities he had founded. They deal with issues of theology and morals, and provide words of correction and encouragements.

The Catholic Epistles

20. James (Jacob), 21. I Peter, 22. II Peter, 23. I John, 24. II John, 25. III John, 26. Jude

We call these the Catholic Epistles because they are addressed to the whole Church (the word katholikē means ‘whole’ or ‘complete’) rather than specific communities.

Apocalypse

27. Revelation of John

This book describes a vision revealed to St John the Apostle (the word apokalypsis means revelation). It is a series of symbolic visions relating to the past, present, and future of the Christian Church. In particular, it deals with the renewal of the world and the ultimate triumph of good over evil. Due to its complex content, it is not read liturgically in the church, but much of our liturgical symbolism is drawn from it.

How to read the Bible

Since the books of the Bible are so different in form, content, and context, they cannot all be read in the same manner — for example, it would be wrong to read the symbolic visions in Daniel and Revelation in the same way one reads the eye-witness accounts of the Gospel.

More broadly, we identify three primary levels of interpretation:

- The literal — the plain meaning of the text. For example, Moses leading the people out of Egypt as a historical event.

- The allegorical / typological — the symbolic or prophetic significance of the text. For example, Moses leading the people out of Egypt as a type of Jesus Christ freeing humanity from slavery to the devil.

- The spiritual — the personal meaning of the text. For example, Moses leading the people out of Egypt, wandering in the desert, and into the Holy Land, is a symbol of the three stages of spiritual life: the initial grace, the withdrawal of grace, and the return of grace. This third level of interpretation can only truly be understood experientially.

Scripture and Tradition

The word tradition (parádosis) means that which has been handed down. In his second Epistle to the Thessalonians, St Paul says: ‘Therefore, brethren, stand fast, and hold the traditions (paradóseis) which ye have been taught, whether by word, or our epistle’ (2:15).

The books of the Bible form part of a wider Sacred Tradition, which includes other things that the Apostles and Fathers have handed down to us, such as the celebration of the Eucharist or the making of the Sign of the Cross. This Holy Tradition is different from the ‘traditions of men’ — human inventions that obscure rather than uphold the revelation of God — that Jesus tells us to reject (Mark 7:8).

While the Church encourages us all to read the books of Scripture as often as possible, we must interpret them in the light of the wider Tradition of which they are a part to ensure that we understand them correctly. The Church did not come out of the Bible, the Bible came out of the Church.

Is there life after death?

What is death?

Human beings are psychosomatic, we are a union of soul and body. Death is the dissolution of this union, the separation of the body from the soul. Our bodies are composite — made up of different parts — and this is why, after the moment of death, the body begins to decay and dissolve into its constituent elements, returning to the earth from which it was taken. The soul, however, is simple — it is not made up of parts — and therefore doesn’t suffer decay the way the body does, but remains intact even after death.

The Bible says clearly that, ‘God did not make death: neither does he take pleasure in the destruction of the living. For he created all things, that they might have their being […] For righteousness is immortal: But ungodly men with their works and words called it to themselves’ (Wisdom of Solomon 1:13-16). We were not made for death, but brought death upon ourselves by sin (i.e., by turning away from the Source of Life, which is God). God did not make us naturally mortal nor naturally immortal, but gave us the choice to choose mortality or immortality. When mankind chose death, he allowed this ‘in order that evil might not exist forever’. However, he did not abandon us to death, but gave us also the possibility of restoration and immortality by becoming man in the person of Jesus Christ.

What does the Bible say about life after death?

While the Bible speaks frequently about the future resurrection of the dead, it does not focus much on the experience of the soul after physical death (i.e., while it awaits reunification with the body at the resurrection). It is not completely silent, however, and the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16) in particular provides us with some important insights:

- The soul of the righteous is escorted by angels (16:22). Elsewhere in Luke, we see the soul of an unrighteous person being required by the demons (12:20).

- The soul remains conscious and retains its personhood .

- It experiences a state of comfort — the ‘Bosom of Abraham’ — or torment, described as Hades (16:23).

- It remembers its life on earth (16:25), and retains attachments to loved ones (16:27-28).

The moment of death

During the Midnight Office on Saturday, we pray:

‘O Master, let Thy hand shelter me and let Thy mercy descend upon me, for my soul is distracted and pained at its departure from this my wretched and defiled body, lest the evil design of the adversary overtake it and make it stumble into the darkness for the unknown and known sins amassed by me in this life. Be merciful to me, O Master, and let not my soul see the dark countenances of evil spirits, but let it be received by Thine Angels bright and shining’.

Essentially, we continue to keep in death the company we kept in life. If we spent our lives in the company of angels — that is, a life of faith in Christ — those same angels will come to escort our soul at the moment of death; if we spent our lives in the company of demons — a life of selfishness, rejection of God, and indifference towards our fellow man — these are the ‘friends’ we will encounter at death.

This, of course, is not something that occurs only at death. The invisible world always surrounds us. However, we are generally not aware of this fact because we perceive the world around us through the physical senses of the body. When the soul leaves the body, however, it can see only with its own ‘senses’, and therefore becomes aware of this angelic presence.

The particular judgment

The presence of angels and demons at the moment of death also represents our conscience being reminded of our good and bad deeds and dispositions. No longer blinded by the false comforts and vain preoccupations of this world, we are suddenly able — to some extent, at least — to see the truth of who we are. If we have not already repented and come to terms with our flaws and shortcomings, this will be an unpleasant experience; a form of judgement.

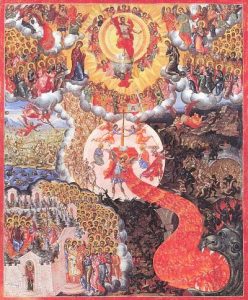

This particular judgement of the conscience — as opposed to the General Judgement, where all will stand before the Judgement Seat of Christ — will determine whether this temporary state of the soul, as it awaits its reunification with the body, will be experienced as bliss or torment. Both these experiences are not Heaven and Hell, but a partial foretaste of these two states.

Praying for the dead

Just as the souls of the dead remain conscious and retain an awareness (or at least a memory) of those it left behind, so we remain aware of those who have departed from us, and pray for them: that they may be granted rest with the saints, and that they may not suffer condemnation on the Day of Judgement.

Unlike the Latin church, the Orthodox Church does not have a concept of Purgatory, where this intermediate state constitutes a process of purification by fire.

Resurrection and Judgement

In the Creed, we confess that Jesus ‘is coming again in glory to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom will have one end’. We also add: ‘I await the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the age to come’

St Paul explains that, when Christ returns in glory, the dead will rise first, so that all people — those who are alive at the time and those who had already died — can ‘meet the Lord in the air’ (1 Thessalonians 4:15-17), just as it was the custom for the inhabitants of a city to go out and meet the king as he approached.

Just as Christ’s resurrection was a physical resurrection (Luke 24:39), this general resurrection of the dead will also be a physical resurrection, a reunion of soul and body, and the return of the human person to its natural unified state.

The Judgment, then, is not a judgement of souls, but a judgment of the whole human person — body and soul — because the life for which we are judged was not lived only by the soul, but by the whole human person. Moreover, the eternity into which we enter after that Judgement is not a disembodied spiritual reality, but an existence that also involves the body (albeit in transfigured and perfected form). This applies not only to our bodies, but to the entire physical world, which will be renewed: ‘For, behold, I create new heavens and a new earth’ (Isaiah 65:17).

Heaven and Hell

God is perfect and self-sufficient, he isn’t subject to change, and we cannot speak of God as having human emotions. The Bible does use anthropomorphic language and attribute emotions to God — God being angry, for example — but these are poetic devices. God is love in his very being, and that perfect love cannot be affected by our actions. That’s why Christ says, ‘Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be sons of your Father in heaven. He causes His sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous’ (Matt. 5:45). God has the same love for the holiest saint and the most terrible sinner.

This likewise applies to the Orthodox view of heaven and hell. When we speak of Judgement, this involves our coming into the presence of God, seeing him as he is (1 John 3:2), and simultaneously seeing ourselves for who we truly are. How we experience this encounter, and the accompanying self-realisation, is what we describe as ‘heaven’ and ‘hell’.

As the Fathers of the Church teach, the light of heaven and the fire of hell are the same thing: the presence of God. A person who has spent their life in total darkness, and then suddenly steps out into a bright light, will find that light intolerable and excruciating. A person whose eyes are adjusted to the light, on the other hand, will experience that very same light as something joyous and pleasant. So it is with the light of God.

Hell, then, is not a manifestation of God’s hatred or lack of forgiveness, but rather his absolute respect for human freedom, without which love — and therefore heaven — would be impossible. As the author C.S. Lewis once wrote: ‘The gates of hell are locked on the inside’.

What is Orthodox Christianity

What is the Orthodox Church?

The Orthodox Church is the original Christian Church described in the pages of the New Testament. Her history, faith, and way of life can be traced in unbroken continuity all the way back to Christ and his Twelve Apostles.

The Greek word Orthodoxía comes from two words: orthós, which means straight or correct, and dóxa, from dokeín, which means opinion or belief. So ‘Orthodoxy’ simply means ‘correct belief’, and we use this word to distinguish the genuine unchanged faith from the various confessions that have changed or deviated from the original Apostolic teaching and tradition.

In other words, ‘Orthodoxy’ and ‘Christianity’ are synonyms. The Orthodox faith is the Christian faith revealed to mankind by God through the prophets and the Apostles, the Orthodox Church is the Christian Church founded by Jesus Christ. Thus, Orthodoxy is not an exotic variant of Christianity, not a conservative alternative to mainstream Christianity, not one Christian denomination among many, nor a particular cultural expression of Christianity — it’s Christianity, full stop.

What is meant by the term ‘Greek Orthodox’?

The term ‘Greek Orthodox’ — also ‘Roman Orthodox’ — refers to the particular liturgical tradition that developed in the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire (as opposed to the Latin-speaking West). Greek Orthodox Christians, then, are those Orthodox Christians who worship according to the Eastern Roman (‘Byzantine’) rite.

The Nicene Creed

The Symbol of Faith

The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed

I believe in one God, Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Only-begotten Son of God, begotten from the Father before all ages; Light from Light, true God from true God; begotten, not made; of one essence with the Father; by Whom all things were made. Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary, and became man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate, suffered, and was buried; and on the third day He rose again according to the Scriptures; and ascended into heaven, and sitteth at the right hand of the Father; and He shall come again, with glory, to judge both the living and the dead; Whose Kingdom shall have no end;

And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of Life; Who proceedeth from the Father; Who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified; Who spoke by the Prophets; in One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church. I confess one baptism for the forgiveness of sins. I await the resurrection of the dead and the life of the age to come.

Amen.

The Symbol of Faith was formulated at the two first Ecumenical Councils (held at Nicea in 325 A.D. and Constantinople in 381 A.D.) and summarises the basic doctrines of the Christian faith. It is first and foremost a baptismal Creed, constituting the confession of faith made before a person is baptised and becomes a member of the Church, the Body of Christ. We repeat and reaffirm this confession at every Divine Liturgy, and daily during our morning and evening prayers.

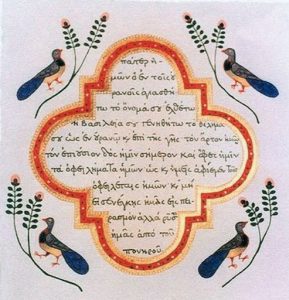

The ‘Our Father'

The Lord’s Prayer

Our Father, who art in the heavens, hallowed be Thy name. Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one.

The Lord’s Prayer is so called because we were taught to pray it by our Lord Jesus Christ himself (Matthew 6:9), for which reason it is the most important and most frequently recited prayer used in Orthodox worship services. Below is a short explanation of its meaning.

Our Father, Who art in the heavens

In one sense, everyone can describe God as their Father, since he is the maker of all things. When Christians refer to God as Father, however, they mean first and foremost that he is the Father of his only-begotten Son, our Lord Jesus Christ. While Jesus alone can call God ‘Father’ in a true sense, the same privilege is granted to us when we become God’s children by adoption, when we are united to Jesus Christ as members of his Body, the Church, through baptism and the Eucharist.

To “dare to call upon the God of heaven as Father”, as we say in the Liturgy, is thus a great gift of grace, given to baptised members of the Christian Church.

Hallowed be Thy name

In the Gospels, Jesus exhorts us: “Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in the heavens” (Matthew 5:16).

What we are asking for here, then, is for God to help us live in such a way that our lives become witnesses to his grace in us, thus bringing others to faith in him.

Thy kingdom come

God’s kingdom is his presence. We are here praying for him to come into our lives, into our hearts, and be present with us in every moment (“Behold, the kingdom of God is within you” – Luke 17:21).

Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven

Just as the angels of God do his will in heaven, we pray that God will help us to manifest his will — his love, peace, justice — here on earth.

Give us this day our daily bread

The Greek usually rendered ‘daily’ here is epioúsion, which literally translates to ‘super-essential’. In this petition, we are praying that God provides us with our basic needs each day, but we are also asking for that Bread which is ‘above the essence’: Christ himself. This is one of the reasons the Lord’s Prayer is recited just before we receive Holy Communion in the Liturgy.

“I am the bread of life; he who comes to Me will not hunger, and he who believes in Me will never thirst” – John 6:35

and forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors

Our Lord tells us: “For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged, and with the measure you use it will be measured to you” (Luke 7:2) and “if you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you” (Matthew 6:14).

Quite simply, God will treat us as we treat others.

and lead us not into temptation

The Bible says clearly that “God cannot be tempted with evil, and he himself tempts no one” (James 1:13). Why then, do we ask God not to lead us into temptation? The Greek here uses the aorist subjunctive of eisphérō, and so the idea being expressed is therefore ‘Do not allow us to be tempted’.

It should also be noted that the Greek word peirasmos has broader connotations than the English ‘temptation’, and can also mean something like ‘trial’.

but deliver us from the evil one.

The Greek word poneirou here can be both masculine or neuter, and therefore ‘deliver us from evil’ and ‘deliver us from the evil one’ (i.e., the devil) are equally valid translations.

What is prayer?

‘Prayer is infinite creation, far superior to any form of art or science. Through prayer we enter into communion with Him that was before all worlds. Or, to put it another way, the life of the Self-existing God flows into us through the channel of prayer. Prayer is an act of supreme wisdom, of all-surpassing beauty and virtue. Prayer is delight for the spirit’ — St Sophrony of Essex

What is prayer?

Prayer, in short, is our way of communicating with God. Prayer can take many forms — silence and song, formal and informal, formulaic and extemporaneous, public and private, at night and during the day, in church and at home.

Prayer is as essential to the soul as oxygen is to the body, it is the thing that makes us truly human, and constitutes our ultimate purpose and goal.

Types of Prayer

Corporate prayer — this is prayer as part of a group. In order to ensure that everyone can participate without distraction and confusion, corporate worship usually only takes place in the context of a church service — ‘For God is not the author of confusion, but of peace, as in all churches of the saints’ (1 Corinthians 14:33). Some services, like the Divine Liturgy, require the participation of a priest, others, like the Compline, do not.

Please see the Divine Services section on this website for an overview of the different services / daily prayers.

Individual prayer — strictly speaking, there is no such thing as ‘individual prayer’, because even when we are physically alone, prayer nonetheless connects us with the other members of the Body of Christ (we always pray ‘Our Father’, never ‘My Father’).

When we pray alone, we should also keep to a certain formal structure of prayer. By reciting the words of Scripture and prayers written by the saints, we learn how to pray — how we should see ourselves and what we should ask for — and we will often find that the prayers written thousands of years ago express the way we feel much better than we ever could. Using the same prayers as our brothers and sisters also helps us to feel that connectedness with the rest of the Church. Most prayer books will contain a collection of morning and evening prayers (usually based on the Midnight Office and Compline respectively).

That being said, we are also encouraged to pray freely, expressing to God with our own words (or no words at all) the state of our heart. Not only during the times we specifically set aside for prayer, but throughout the day, regardless of where we are or what we might be doing. Every moment is an opportunity for prayer!

The Icon corner

An Orthodox household will normally have an icon corner (some refer to this as a ‘home altar’), though it needn’t be an actual corner. This is where the family will gather for their daily prayers. It should ideally face East, since this is the direction we face during prayer. The icon corner will usually feature a Bible, a Cross, and icons of our Lord, the Virgin Mary, John the Baptist, and the patron saints of those in the household. One will normally also have an oil lamp — lit during prayer, if not continuously — and a small incense burner. An icon corner can be very elaborate or very simple; the important thing is that it inspires in us a feeling of reverence and a desire to pray.

The sign of the Cross

Our prayers are accompanied by the sign of the Cross. The sign of the cross is made by joining the thumb, index finger, and middle finger on the right hand — this symbolises our faith in One God who exists as three hypostases: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. At the same time, we join our ring finger and little finger, and push these down towards our palm — this symbolises the two natures of Christ, divine and human, and His coming down to earth.

We then touch our fingers to our forehead, our belly, our right shoulder, then our left shoulder in order to make the sign of the Cross over ourselves. Besides being a confession of our faith in Christ’s saving work on the Cross, the hand movement itself also expresses the Gospel message: God in heaven (forehead) came down to earth (the belly), He who sits at the right hand of the Father (right shoulder) came to save us sinners on the left (left shoulder).

The sign of the Cross is normally made at the conclusion of a prayer, when the Name of the Trinity is invoked — Father (forehead), Son (belly), and Holy Spirit (shoulders) — but there are no strict rules regarding when the sign of the Cross should or shouldn’t be made.

Bows and prostrations

Human beings are psychosomatic — a union of soul and body. For this reason, the participation of the body in prayer is essential. Bows and prostrations play an important role in this respect. In Greek, these are referred to as metánies (literally, repentances).

A bow (small metánia) is performed by making the sign of the Cross as described above, and then bowing forwards from the waist. We will often stretch our right hand toward the ground as an expression of humility, reminding ourselves that ‘All go unto one place; all are of the dust, and all turn to dust again’ (Ecclesiastes 3:20).

A prostration (great metánia) is made by getting down onto one’s hands and knees, and touching one’s forehead to the ground. We see this posture of prayer mentioned frequently in the Bible. Jesus ‘fell on his face and prayed’ in the Garden of Gethsemane (Luke 5:12), as did Abraham (Genesis 17:3), Moses and Aaron (Numbers 20:6), Joshua (7:6), Ezra (Nehemia 8:6), Ezekiel (1:28), King David (1 Chronicles 21:16), etc. In addition to being an expression of awe and humility, prostrations also express a very basic characteristic of spiritual life: we fall and get up again.

In the context of common worship, prostrations are usually limited to certain moments in the services (such as the Prayer of St Ephrem during Lent, or at the Consecration of the Holy Gifts at the Divine Liturgy). In private, however, it is common to incorporate a number of prostrations into one’s daily prayer rule.

We do not perform prostrations on Sundays, but remain standing in honour of the Resurrection.

‘Lord, have mercy’ (Kyrie, eleison)

If you ever attend an Orthodox service, you will immediately notice how frequently the phrase ‘Kyrie, eleison’ (Lord, have mercy) is used. This is the response to almost every petition uttered by the priest or deacon, and in some services the forty-fold repetition of ‘Kyrie, eleison’ is used as a prayer in its own right.

In the Bible, the Greek word éleos (mercy) is used to translate two Hebrew words: ḥesed (חסד — steadfast love or kindness) and reḥem (רחם — compassion).

The second word, reḥem, literally means ‘womb’. The biblical idea of compassion, then, is that of a mother’s love for the child in her womb, and all that the unborn child receives from her: nourishment, warmth, safety, growth, and so on.

The prayer ‘Lord, have mercy’, then, is used so frequently because it is all-encompassing; it expresses our every need. It has been said that ‘Lord, have mercy’ is the only prayer of the Church; all else is commentary.

The Jesus Prayer

This prayer also comes in a longer form: ‘Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner’ (or, commonly, ‘Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me’).

This is what we know as the ‘Jesus Prayer’ (or simply, ‘The Prayer’), and it forms the bedrock of Orthodox spirituality; what we know as hesychasm (‘the practice of stillness’).

As we said above, prayer is the oxygen of the soul, and prayer should therefore be as constant as our breathing. When St Paul says, ‘Pray without ceasing’ (1 Thessalonians 5:17), we take this literally, and our goal in prayer is to attain to a point where the words of prayer become constant within us, even while asleep.

The same Apostle tells us, ‘Whatever you do in word or deed, do all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through Him’ (Colossians 3:17). Therefore, this unceasing prayer consists in our unceasingly calling upon the name of the Lord Jesus — ‘the name which is above every name’ (Philippians 2:9) — and combining this with the all-encompassing prayer for mercy.

This, of course, not something that we can attain merely by human effort; it is a work of the Holy Spirit.

A prayer rope — similar in appearance to a rosary, but usually made out of woolen knots rather than beads — is normally used when saying the Jesus Prayer. The point of the rope is not so much to count the number of repetitions (which is not itself important), but to aid concentration.

The three stages of prayer

The tradition of the Church identifies three main stages of prayer:

- Prayer of the lips — reciting the words of the prayer.

- Prayer of the mind — reciting the words of the prayer with understanding and an awareness of what it is you are expressing.

- Prayer of the heart — this is the state of pure prayer, undistracted by images or concepts. It is, if you like, a ‘direct line’ to God.

The Lord says, ‘Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God’. Everything in spiritual life is aimed at this purification of the heart. When we are far from God, the eyes of the heart are blinded by the fog of sin. As we turn away from sin and move towards what is good, through prayer and the keeping of God’s commandments, this fog dissipates, and we become increasingly aware of God’s presence in our life (as well as of our own shortcomings, which is why holiness is always accompanied by great humility).

Who are the saints?

Who are the saints?

In a broad sense, all the members of the Church are called ‘saints’ (hagioi, holy ones) because we belong to Christ, who is holy, and are called to attain to his holiness — ‘Be holy for I am holy’ (1 Peter 1:16). In the Divine Liturgy, for example, the priest lifts up the consecrated Bread, the Body of Christ, and exclaims, ‘The holy things for the holy’ (i.e., ‘for the saints’). The ‘saints’ referred to here are those about to receive Holy Communion. Likewise, the Apostle Paul, writing to different Christian churches, addresses his letters ‘to the saints which are in Ephesus’, ‘to the saints which are in Christ Jesus at Philippi’, and so on.

In a narrower sense, however, we use the word ‘saint’ to describe those members of the Church having attained that holiness. These are men and women from all walks of life, of every age, race, and class: ‘Forefathers, Fathers, Patriarchs, Prophets, Apostles, Preachers, Evangelists, Martyrs, Confessors, Ascetics, and every righteous spirit made perfect in faith’.

‘Above all’, we honour ‘our all-holy, pure, most blessed and glorious Lady, Mother of God and Ever-Virgin, Mary’, who, on account of her great virtue, was chosen by God to be the vehicle of his incarnation, the ladder by which he would descend to earth from heaven.

Do you worship the saints?

Our Lord tells us unequivocally: ‘You shall worship the Lord your God, and Him only you shall serve’ (Luke 4:8). The Orthodox Church teaches clearly that God alone is worthy of adoration (latreia).

We can and should show reverence to holy things — we treat the Bible or the Cross with great respect, for example. The same goes for those righteous men and women held in high esteem by the Church, just as we show honour and affection for the people we love and respect here on earth. How could we not show honour to the woman who gave birth to God in the flesh, or to the man who baptised him in the Jordan, to the prophets who spoke with God ‘face to face, as a man speaks to his friend’ (Exodus 33:11), or to the martyrs who gave their life for the sake of the Gospel of Jesus Christ?

Worship, however, belongs solely to God the Holy Trinity.

Don’t you pray to the saints?

In the Gospels, Jesus says, ‘Most assuredly, I say to you, he who hears My word and believes in Him who sent Me has everlasting life, and shall not come into judgment, but has passed from death into life’ (John 5:24). Elsewhere, he reminds the people that God had said, ‘I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’, and adds, ‘He is not the God of the dead, but the God of the living’ (Mark 12:26-27).

The saints, then, though they have undergone physical death, are alive in Christ. And as living members of the Church, they are also included in the biblical exhortation ‘pray for one another, that you may be healed. The effective, fervent prayer of a righteous man avails much’ (James 5:16). Since the prayers of the righteous avail much, it is natural that we should ask the saints to pray for us.

In other words, because we believe that our God is ‘not the God of the dead, but the God of the living’, we ask the saints to pray for us in the same way that we ask other members of the Church to pray for us.

Why don’t you just pray directly to God?

The answer to this is that we do pray directly to God. Asking others to pray for us — whether they be saints in heaven or friends on earth — is not something we do instead of praying to God, but something we do in addition to praying to God; it’s not either/or. And we do so because God has told us to: ‘pray for one another’. Love of God is inseparable from love of neighbour, and our relationship with God is not something that takes place in isolation from others, but in the context of our membership of the Church, the Body of Christ. This is why the Bible tells us to ‘confess our sins one to another, and pray one for another‘ (James 5:16) and to ‘carry each other’s burdens’ (Galatians 6:2).

Feasts and fasts

The rhythm of Orthodox life is regulated by the Church calendar, which leads us through the year through a carefully balanced cycle of festal periods and fasting periods.

The Great Feasts

While every day of the year is devoted to a particular saint or event, certain feasts of our Lord, of the Virgin Mary, of St John the Baptist, and of the patron of each parish or monastery are considered great feasts.

On these days, the Church calls us to rest from secular work (if we can), so as to attend the related divine services and more generally devote the day to God, in fellowship with our family and our brothers and sisters in Christ. Below is a list of some of the main feast days of the Church year.

8th September — Birth of the Virgin Mary

14th September — Exaltation of the Holy Cross

23rd September — Conception of St John the Baptist

21st November — Entry of the Virgin Mary into the Temple

30th November — St Andrew the First-called Apostle (parish feast)

9th December — Conception of the Virgin Mary by St Anna

25th December — The birth of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ according to the flesh

1st January — The Conception of our Lord

6th January — Theophany: the Baptism of Christ in the Jordan River

2nd February — The Meeting of the Lord in the Temple

25th March — The Annunciation of the Virgin Mary (Conception of our Lord)

Palm Sunday (the Sunday before Easter)

Holy Pascha / Easter Sunday — the Resurrection of our Lord

The Ascension of the Lord — 40 days after Easter

Sunday of Pentecost — 50 days after Easter

24th June — Birth of St John the Baptist

29th June — The Apostles Peter and Paul

6th August — The Transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor

15th August — The Dormition of the Virgin Mary

Fasting

In the Gospels, Jesus does not say ‘If you fast’, but ‘When you fast’ (Matthew 6:16). He takes it as a given that fasting is part and parcel of spiritual life. For this reason, the Church calendar also sets aside certain days and periods as times of fasting: abstinence from food or drink — or types of food and drink — for a certain period of time, although fasting is about much more than food.

Why do we fast?

We fast for a number of reasons:

- Love for the poor — Fasting must not be a self-centered act, and is always accompanied by charity. By eating less and eating more simply, we have more left over for others. The same is true of time and money saved on entertainment; we can spend them on others and on God. The experience of voluntary hunger and deprivation should also kindle in us compassion for those who experience these things involuntarily.

- Freedom — While modern society tends to understand freedom as the ability to do whatever you want whenever you want, a person who lives in this way is really just a slave to their impulses, being dragged every which way like a dog on a leash. True freedom comes with self-control, and the ability to choose the good. Learning to control our most basic impulses — such as food and sex — is a way to break free from our passions and help us to attain true spiritual freedom.

- It helps us to pray — We are psychosomatic beings, a union of body and soul. How we use our bodies, including how and what we eat, can help or hinder our spiritual progress.

- To remember paradise — death is a consequence of the fall, and the killing of animals for food is something that did not take place until after Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden. By abstaining from animal products, we remember the state of mankind before the fall, and express our longing to return to it.

- Obedience — The cause of our fall from Paradise was pride. It was pride that caused Adam and Eve to disobey the only commandment they were given: a commandment to fast (‘Do not eat of the tree’). The way to our restoration, therefore, is humility and obedience. Observing the Church’s periods of fasting helps us to learn blessed obedience rather than egotistical self-will.

When do we fast?

More than half the days of the year involve some kind of fasting, but not all are very strict.

- Almost every Wednesday and Friday throughout the year

- The Nativity Fast — 15th November to 24th December.

- Great Lent and Holy Week

- The Apostles’ Fast — Monday after All Saints until 28th June

- The Dormition Fast — 1st to 14th August

- Elevation of the Cross (14th September), Eve of Theophany (5th January), Beheading of St John the Baptist (29th August).

We also fast from all food and drink from midnight on any day we intend to receive Holy Communion.

How do we fast?

How we fast is something that varies greatly from person to person. Each person should fast according to their own strength and spiritual maturity, and should work out their particular rule of fasting with the guidance of their spiritual father. In practice, this rule may be much more lenient (or much stricter) than the traditional standard described below:

- Total fast — days on which we traditionally eat nothing at all. These include the first three days of Great Lent and Holy Friday.

- Strict fast (no oil) — on days of strict fasting we abstain from food and drink until the 9th Hour of the day (3pm). After that, we eat a single meal, which should contain no meat, eggs, dairy or fish. Also, the food is not to be prepared with oil, but should be as simple as possible (raw or boiled). Alcohol is not to be consumed.

Strict fasting is observed on most Wednesdays and Fridays, weekdays of Great Lent and the Dormition Fast, and the last ten days of the Nativity Fast.

- Oil and wine — on ‘oil and wine’ days we keep to a vegan diet, but we eat a normal number of meals. The food can be prepared with oil, and alcohol (in moderation) may be served with the meal.

This type of fasting is observed on Saturdays and Sundays of Lent, or if a feast day falls on a day of fasting.

- Fish — Same as ‘oil and wine’ days, but fish is also permitted.

This type of fasting is observed when an important feast falls during a fasting period — e.g, the Annunciation in Lent or the Transfiguration of the Lord during the Dormition Fast. It is also observed throughout the Apostles’ Fast and the first month of the Nativity Fast.

On all days of fasting, married couples also abstain from sexual relations, but this must be done by mutual consent (1 Corinthians 7:5).

Remember

It should go without saying that fasting is a means to an end, not an end in itself, and that the inward disposition with which we fast is much more important than the outward form we observe. Moreover, fasting from food is of no use if we are eating the flesh of our brother through gossip and hatred. No act of asceticism will bear fruit unless it is accompanied by prayer, charity, love, forgiveness, and humility.

Joining the Orthodox Church

Who can become Orthodox?

Our Lord commanded us to ‘make disciples of all nations’ (Matthew 28:19). The Orthodox Church is open to everyone, regardless of age, sex, nationality, race, ethnicity, colour, or class. The only requirement is that you believe in Jesus Christ and recognise that membership of the Orthodox Church is membership of His Body, accepting the divinely revealed truths it has preserved for two thousand years through its teachings and practices.

How can I become Orthodox?

If you are interested in joining the Orthodox Church, please get in touch with us by telephoning the church office or sending us an e-mail. Reception into the Church must be preceded by a period of catechesis (religious instruction), the content and duration of which will depend on your prior knowledge and personal circumstances.

Recommended reading

Introduction to Orthodoxy

Alfeyev, Hilarion, The Mystery of Faith: An Introduction to the Teaching and Spirituality of the Orthodox Church (DLT, 2002).

Alfeyev, Hilarion, Orthodox Christianity, vols. 1–5 (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011–19).

Bartholomew, His All Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch, Encountering the Mystery: Understanding Orthodox Christianity Today (Doubleday Books, 2008).

Hieromonk Gregorios, The Orthodox Faith, Worship, and Life (Cell of St John the Theologian, Mount Athos, 2016).

Hierotheos, Metropolitan of Nafpaktos, Entering the Orthodox Church: Catechism and Baptism of Adults (Birth of the Theotokos Monastery, 2004).

Hierotheos, Metropolitan of Nafpaktos, The mind of the Orthodox Church (Birth of the Theotokos Monastery, 1998).

Louth, Andrew, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology (IVP Academic, 2013).

McGuckin, John Anthony, The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

Metallinos, George, The Way, an Introduction to the Orthodox Faith (Holy Meteora, 2013).

Pomazansky, Protopresbyter Michael, Orthodox Dogmatic Theology (St Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2009).

Ware, Kallistos, The Orthodox Way (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2002).

Ware, Timothy (Kallistos), The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Eastern Christianity, 3rd edition (Penguin: 2015).

Life after death

Hierotheos, Metropolitan of Nafpaktos, Life After Death (Birth of the Theotokos Monastery, 1996).